Biography of the Founder, Dr. Muhammad Iqbal

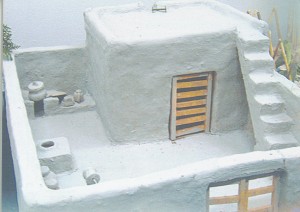

I was born in 1930, in a one-room mud-house in Sukho, a Sikh-majority village near Gujar Khan – in what is now Pakistan. In that village all merchants were Sikh, except one lonely Muslim running a tobacco shop. My father was a brick-layer, a trade he learned as a very young orphan, while my uncle learned tailoring at the same time. Most of our relatives were poor illiterate labourers.

I spent the first two years of primary school in my native village, and then the family moved to the Lahore Cantonment where I grew up, in small rented houses, one after another. At one point our one-room rented house was not much larger than the living room of my current Canadian home. At night I did my school work under a linseed oil lamp or a kerosine lamp. Nevertheless, I had a very happy childhood.

When I was growing up, my relatives would affectionately call me “babu”, meaning clerk. For them it was their dream that, one day, one of their own would complete Matric (Grade 10) and have an office job, sitting under shade instead of toiling in the sweltering heat digging ditches. Their dreams came true beyond their imagination.

We are seven siblings, four girls and three boys, spread over twenty years of age difference. I am the second eldest, and my two brothers are the youngest in the family. Two of the elder girls were not allowed to go to school. “If they get educated, they would rebel”, was the view of senior males in the family. However, as soon as I started earning I helped my two younger sisters to continue their studies into college, one ending up studying medicine and the other economics. That improved our social standing in the community but not our wealth.

My father continued working as a mason until his retirement. He was always called “mistry” Bostan. In Urdu/Punjabi “mistry” means brick-layer. However, after his retirement he bid on a construction contract and made a huge profit. All of a sudden we jumped from upper-poor-class to upper-middle-class! My father bought four residential plots of land and built a huge house on two plots, with each room having its own en-suite bathroom. Gone were the days when we would go behind bushes when nature called. My father went to Mecca to perform Haj and thereafter, as a mark of respect, he was addressed as Haji Bostan Khan Sahib; a big change in his, and that of family’s status. My father became chief patron of the local mosque.

I went to Islamia High school, Lahore Cantonment, and then to Islamia College, Railway Road, Lahore, both run by local Muslim communities. After obtaining my Bachelor’s degree (1950), I was very lucky to receive admission to the Punjab College of Engineering and Technology, Lahore. As my parents were poor, throughout my studies I received concessions in fees.

After graduating in mechanical engineering in 1953 I worked for a year in the Thal Development Authority, digging tube wells to make the desert bloom. Those days, young men like me were always looking for jobs in foreign firms, and there were plenty of such jobs. I was hired as a sales engineer by a European firm in Karachi, and in 1955 I was sent to West Germany for a two-year training in thermal power plants. That stay in Europe, a well-organized society where everything worked, impacted me a lot. I also took advantage of that stay to learn some German. After almost 60 years, I am still at ease traveling in German speaking countries.

After I came back from Germany, one day, by chance, I met a young fellow of my age whom I knew a bit. We went to a tea house. He had a big brown envelope with him and said that he was applying for studies in America. He explained to me how one can receive a teaching assistantship or a research assistantship in USA/Canada while studying for a Master’s or a Ph.D. His elder brother had just finished his Doctoral studies in the US financed by research assistantships.

After hearing that I went home and started planning to apply for admission and an assistantship in one of the North American universities. I had to put all my imagination and ingenuity to win – so I started one of the major projects of my life. I went to the British Reading Room in Karachi to consult handbooks and made a list of names of many North American universities with graduate programmes in engineering. I composed a two-page letter pitching my main selling point: I have an exceptional ability in 3-dimentional imagination – hire me as a teaching assistant in engineering drawing. I mailed this letter to 72 universities, spread over two weeks – I did not want all my mail destroyed in a single mail box vandalism, or plane crash. Now, all those university calendars started pouring in. It took me a few months to select about 20 universities to apply for admission and financial assistance. My next concern was to ask my former professors for letters of support. They were very kind to help me. After I mailed completed applications, within three weeks I received, from McGill University, Montreal, an offer of admission and teaching assistantship at a princely sum of $150 a month. This was 1959, my first big break in life. I completed my M.Eng. in 1961, and became a faculty member at Concordia University, Montreal, while doing Ph.D. at the same time at McGill.

The day after handing-in my doctoral thesis I married a French-Canadian lady. Soon after completing my Ph.D. in mechanical engineering (1965), I received an offer of a faculty position from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver – that was my second big break in life.

I am an ardent promoter of education of girls and of gender equality. I helped my then wife to do her Ph.D. in French literature (we divorced in 1986). As a man believing in gender equality I fully participated (changing diapers, babysitting, etc.) in bringing up our daughter while my wife completed her doctoral studies and became a faculty member at the same university. This changed our social life; from then on many of our friends in Vancouver were francophone and francophile. French became our home language. Two sabbatical leaves in France improved my French fluency. French has become so rooted in my family that my two grandchildren’s mother language is French.

Foreign languages attract me. I like the sounds of Spanish and Italian languages, so much so, that I spent about six months of one of my sabbatical years in Madrid, officially doing research in Solar Radiation, but mostly learning the language. It was one of my dreams: to be able to speak Spanish like my erstwhile idol, Fidel Castro. After returning to Vancouver, I traveled to several Latin American countries, visiting universities as a guest speaker in my specialty. I must admit, I was a bit of a snob there trying to impress the Latinos with my “superior” Spanish accent acquired in Madrid, while locals there thought I was Brazilian.

After 31 years of teaching and research at the University of British Columbia I retired in 1996.

During my working life I have lived and traveled in many, many countries. I had no desire to travel any more. I wanted to do something else.

During all my life in the West, I always had an uneasy feeling in my inner self ; my education in Pakistan was supported by the community, but I did not stay there to serve my country. This burden of a moral debt hung on my shoulders. So, with the help of my English-Canadian wife, who also is a co-founder of this Foundation, I founded this organization named after the two grandmothers of my wife, Maria and Helena; hence the name Maria-Helena Foundation.

The Foundation was registered in 1999 and the projects so far accomplished are listed under Projects in this website. As a family-based organization we try to be independent of public support. However, during the 2010 epic floods in Pakistan, just when I had turned 80, I made a personal appeal to the general public to sponsor me to hike up, twenty times, Vancouver’s steepest mountain, Grouse Grind (elevation gain 933 m in 2.9 km distance). I received an enthusiastic response from the Canadian public in support of the flood victims. I even became a celebrity for a few nanoseconds; see the link below.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/story/2010/08/24/bc-iqbal-grouse-grind.html

I feel I have paid back my moral debt to Pakistan, but now I am continuing the social development work there; to leave a better world behind.

I am an enthusiastic hiker and cross-country skier. I have one child, a daughter, who just completed her Ph. D., and I have two lovely grandchildren, 7 and 11 who live five minutes walk from my home. The last decade, while my daughter was doing her grad studies, I was more like a “nanny” of my grandchildren; changing diapers, babysitting and more recently taking them to school and bringing them back home. I have learned all that is to learn about diaper rash. I wonder sometimes whether I could enter Guinness Book of Records as “the man who has changed most diapers”.

It has been a very satisfying life for me; I feel I am truly blessed.

Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal

In November 2012, I received a surprise phone call from Joyce Murray, MP Quadra, informing me that I have been selected to receive Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal. The event was held on Sunday, December 16, 2012, Vancouver, Canada. The citation read:

In November 2012, I received a surprise phone call from Joyce Murray, MP Quadra, informing me that I have been selected to receive Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal. The event was held on Sunday, December 16, 2012, Vancouver, Canada. The citation read:

“Exceptional leadership as a humanitarian and philanthropist, including providing schooling for almost 4000 children, mostly girls, through founding of the Maria-Helena Foundation to provide educational opportunities to disadvantaged children in Pakistan.”

These awards are for Canadians, all across Canada, who have shown outstanding leadership and sustained contributions to communities in Canada or outside Canada.

Faculty Community Service Award

In August 2013 I received news from the University of British Columbia, where I was a faculty member for 31 years that I have been selected to receive the Faculty Community Service Award for promoting literacy in Pakistan. I received this award in a special ceremony held on November 14, 2013. The citation read:

“In 1996 Dr. Muhammad (“Mo”) Iqbal retired from UBC’s department of Mechanical Engineering after enjoying a distinguished career specializing in solar power. After 30 years contributing to education and research in Canada, he now devotes himself to creating opportunities for disadvantaged communities in Pakistan, his country of birth.

Iqbal grew up in modest circumstances in a village near Islamabad, but his academic promise meant he was able to receive an education through scholarships and bursaries. In an environment that was largely hostile to the idea of educating females, he helped his two younger sisters secure an education as well. His support for them was an indication of what would come later, on a much larger scale.

In 1999 Iqbal and his wife, Diane Fast, established the family-based Maria-Helena Foundation (MHF) to provide educational opportunities to disadvantaged children in Pakistan, notably to girls. The logistical and cultural barriers to establishing this endeavor were daunting, but, crucially, Iqbal was able finding the right local partners to work with and set up a board in Vancouver as a base of advice and support.

To date the organization has established several self-sustaining primary schools and two libraries serving more than 3,500 pupils. All the teachers are female. A further 450 very impoverished students are receiving education at temporary home-based primary schools with one teacher, with the foundation paying fees and salaries. In addition, a medical clinic is providing approximately 80 people with low-cost treatments, and two training centers are teaching girls and women needlecraft and sewing.

This has been achieved with limited resources that, especially in the early days, came mostly out of Iqbal’s own pocket. He quickly learned to wring out every cent for its full worth. Nowadays, the foundation has charitable status and receives funding from individual donors and organizations such as the United Way. Each year, a recent UBC graduate in Political Science spends a year with Iqbal at the Maria-Helena Foundation to train for work in International Development, with seven students so far benefitting from this experience.

Iqbal’s desire to help his country of birth is not limited to education. In 2010, at the age of 80, he completed Vancouver’s Grouse Grind hike 20 times to raise funds for Pakistani flood victims. He is a generous and compassionate individual with a deep belief in social justice – a practicing humanitarian who is committed to action and change.”